How Thousands of Native Indian American Children Died at School

Dec 08, 2025The history of modern schooling is paved with atrocities. In 1897, government agents removed thousands of Native American Children from their families, by force. The children were taken to government funded boarding schools in an attempt to blot out their culture and have them conform to Anglo culture.[1] There was an assumption that the colonists were superior and the Indians were savage and uncivilized. In need of proper training.[2] In 1897 Richard Henry Pratt, a US Army Lieutenant, founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Pratt said:

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one… In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”[3]

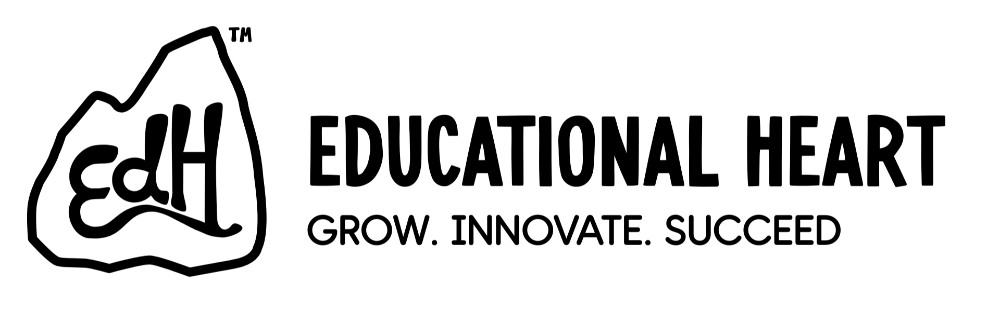

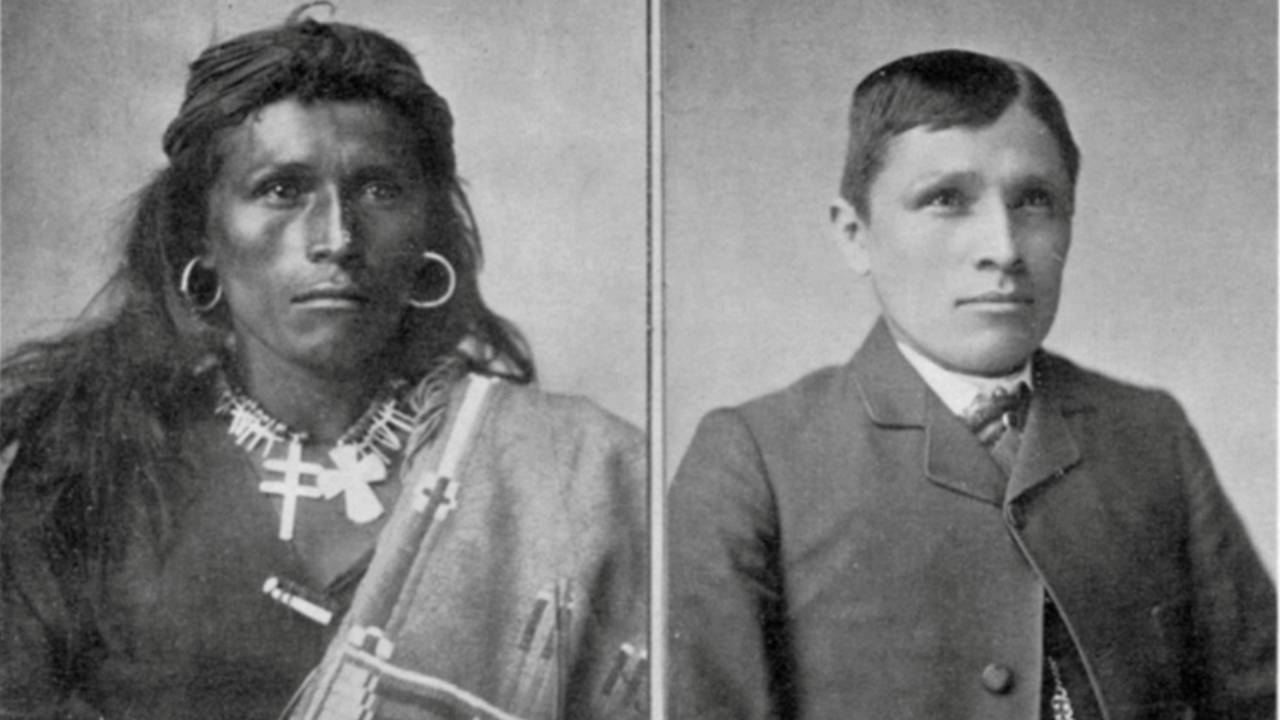

This quote suggests that some people at the time, looked at Indians as savages. Less than human. However, Pratt didn’t view the Person who was Indian as a savage but rather, the Indian culture being the “savage” and the person being distinct. In 1875 prior to the schools founding Pratt ran a program to assimilate Native Americans into white culture while supervising prisoners at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. He used his findings and successful practices from the program, in the boarding school.

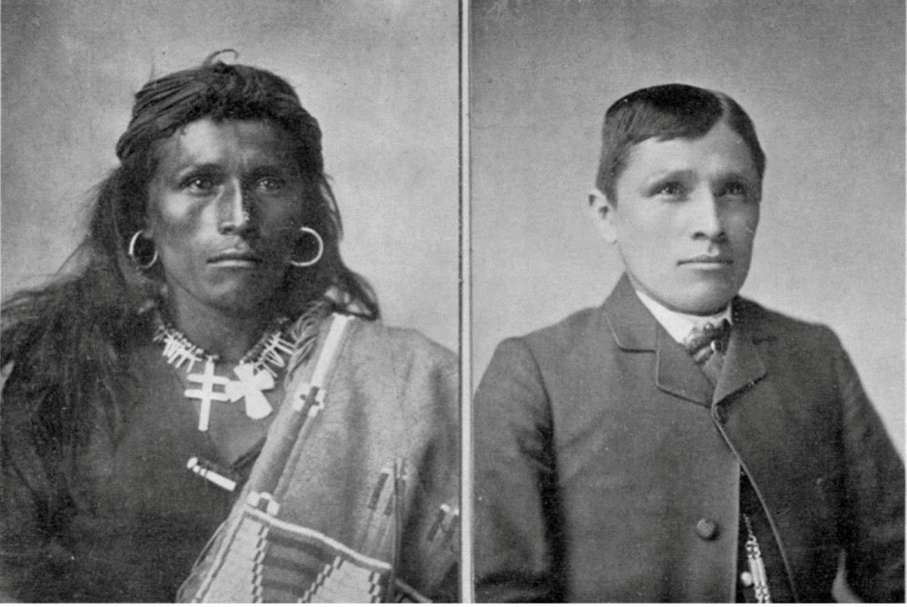

- Native Indian Americans at Fort Marion Before

- Native Indian Americans at Fort Marion After

Evangelism to Assimilation

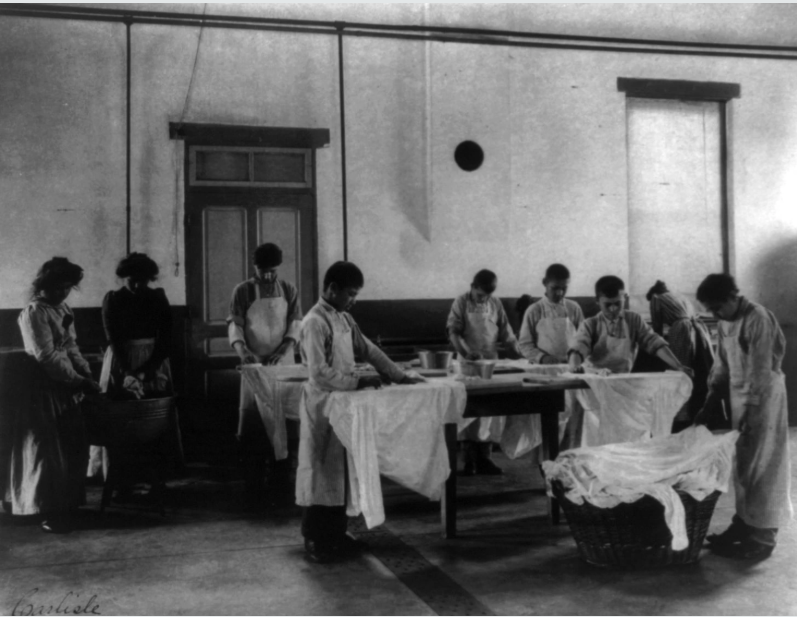

After the Civilisation Fund Act of 1819,[4] Christian missionaries had been a large part of building boarding schools and developing curriculums for Indian students. Even making dedicated school days and times in white schools for the Indian students. The primary focus at the time was evangelism rather than assimilation. After the Removal Act of 1830,[5] and the encouragement of prominent figures such as Pratt, the aims of these schools slowly changed to complete re-education and assimilation. The authority figures in charge of the children, removed all reminders of Native culture.

- Native Indian American Children Cleaning Clothes

Cultural Genocide

The Native children, upon their arrival, had their pictures taken. ‘Caretakers’ then stripped the children of their tribal clothes, and affiliated items: such as medicine bags, jewelry and ceremonial objects. After all physical demarcations of their tribal affiliation were removed, the boys had their hair cut short and were dressed in military uniform. While the girls were forced into skirts and corsets to fit the popular American fashion.[6] To complete their transformation and the annihilation of the Native Indian Cultural Identity, they were given new Anglican names and forced to be photographed once more. These before and after photographs, were used as proof that Native Americans were able to look American and were, therefore, able to integrate into American society if given the proper instruction and education.[7]

- Navajo Tom Torlino, 1882

Keepers of the Children

Many issues began to emerge as the boarding schools became overcrowded and little was done to accommodate or maintain a standard of care. The people who ran the schools, and those who took care of the children weren’t necessarily willing participants. Caretakers were often missionaries, subjected to similar if not the same living conditions as the children. The system was flawed. The Nun, Elizabeth Schoffen, who served at the Tulalip Mission School in Washington state, recounted her five years there beginning in 1884. In her memoir, The Demands of Rome, she stated:

“The accommodations for cleanliness were very poor, and the stench in that sleeping room was simply nauseating, and there was no remedy for it, with the existing conditions. In the morning, I had to dress about twenty-five of these girls, and care for the running, mattering sores of many, who were diseased (scrofulous), with an ointment supplied for that purpose by the government physician.”[8]

There were little provisions given to these schools and little notoriety in the beginning decades.

- Native Indian Boarding School

The Death Toll

Unfortunately, the tragedy didn’t stop there. Not only did these schools run for decades, with the majority of boarding schools’ shutdown by the late 1970s, they also contributed to numerous deaths. A U.S. report, uncovered documents and grave sites indicating almost 1,000 children died in boarding schools across America. Since the report, organizations and advocacy groups have actively sought answers for Native American communities, uncovering additional information through their efforts. The death toll has now risen to almost 4,000 deaths, and rescue teams believe it is likely to continue to rise as they uncover more burial sites.[9]

Documentation Lacking

Officials at the time had supposedly documented the deaths that took place in the Boarding Schools. However, modern investigators have found the remains of many who were not included in that documentation. The current information shows that many children died from malnutrition and sickness, while others resulted from brutal beatings, or people jumping out of windows. Whether some of these events were homicide, an attempt to escape, or suicide is unknown. The lack of details surrounding each case makes it difficult to draw a final conclusion. Many of the children’s names that were recorded are either misspelled, incorrect (because they’re the Anglican names given by the school) or non-existent. The remains of the children, young and old,[10] have been uncovered in grave sites close to the location of old Indian boarding schools. This has causing much grief among the native American community, over the last few years.[11]

Testimonials

Ramona Klein, when speaking to a group at a vigil in Washington September 2025, said:

“When I went to boarding school, I was 7… My parents didn’t see me — other than a little while during the summer — for four years. Some parents didn’t see their children for 12 years… There was physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, academic abuse, intellectual abuse and neglect…”[12]

She also explained that she began to heal for the sake of her children and grandchildren and that:

“If we [referring to survivors] don’t remember what happened, it’s going to get lost… I’m closer to the end of life than the beginning of life [at age 78], so I have to get busy. I have to stay busy so that it’s not forgotten. … We remember all of the survivors, all of the kids who didn’t go home.”

Timeline for the End of These Boarding Schools

By the 1930s, there was a significant decline in these boarding schools due to forced closure, as the public began to know more about these boarding schools. The 1928 Meriam Report, highlighted the criticism over poor conditions, overcrowding, malnourishment, and ineffective education methods within the boarding schools.[13] Still, the system persisted in various forms for decades. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934,[14] marked a policy shift towards Native self-determination, encouraging public school enrolment and community day schools, which aided in the ongoing closure of Indian American schools aimed at assimilation.

However, some boarding schools continued operating well into the late 20th century. The last assimilationist boarding school is noted to have closed in 1978, the same year the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed.[15] Federal support for the boarding school system officially ended around this time and today the U.S. government still operates a small number of boarding schools. As of 2025, there are 125 Indian Boarding schools, none of which serve for the purpose of assimilation, at least not officially.[16]

- One of the many boarding houses in America

Final Thoughts

It is no accident that these schools were able to run for so long, that the inner workings of them were hushed, and that tax payers were unknowing of what their money was actually contributing to. At this point I could talk about the public apology that was given by President Joe Biden, for the treatment of Native Indian Americans during the boarding school decades. But that, in all honestly lacks any real weight. Biden, wasn’t involved in these occurrences directly and those who were are either extremely old or dead.[17] Of course, recognition and acknowledgment is at least a step forward, but it does little to bring true healing or reconciliation.

Closure

The only closure is in: 1) Finding these burial sites. 2) Uncovering and acknowledging the truth of what happened, however uncomfortable that is. 3) Learning all the different circumstances leading to these events. 4) Shifting ones focus to possible solutions and then shedding light on it through the dissemination of information, and 5) Telling people in general conversation when it is suitable to do so. We as a society must continue and move forward together.

The important lessons we learn from these events should never be forgotten and if we are wise, we will compare the purpose of these boarding schools with the compulsory schooling of today. Unfortunately, the purpose isn’t that dissimilar. The difference is the covertness of the purpose. The American public were aware of the purpose of the Indian boarding schools, with marketing clearly showing the assimilation process. Compulsory schools however, are marketed as the golden standard for education, and the only ‘guaranteed’ opportunity for success. But schools are not designed to help children be successful adults, their purpose is to assimilate children into docility, and submission to the government which is explained in more detail here.

Documentaries to Watch

If you’re looking to watch a Documentary about the Native Indian American Boarding Schools here is a link to one by PBS:

Howe, John. Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools (Part One), Documentary, PBS Utah, 56 min, 43 sec. (2016) https://www.pbsutah.org/pbs-utah-productions/shows/unspoken/

References

[1] Feir, Donna L. “The long-term effects of forcible assimilation policy: The case of Indian boarding schools.” Canadian Journal or Economics 49, no. 2(2016): 433-480 https://doi.org/10.1111/caje.12203

[2] Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. “The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: implications for the concept of historical trauma.” Transcult Psychiatry. 51(3) (2014): 320-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461513503380

[3] Adrienne Akins. “‘Next Time, Just Remember the Story’: Unlearning Empire in Silko’s Ceremony.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 24, no. 1 (2012): 1–14. (page 1) https://doi.org/10.5250/studamerindilite.24.1.0001

[4] Crawford, L. “James Monroe’s Trail of Tears.” The James Monroe Museum (2022) https://jamesmonroemuseum.umw.edu/2022/11/28/james-monroes-trail-of-tears/

[5] U.S. Congress. Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History, collection. Library of Congress (1774-1875) https://www.loc.gov/item/llsl-v4/.

[6] Davis, Julie. “American Indian Boarding School Experiences: Recent Studies from Native Perspectives.” OAH Magazine of History 15, no. 2 (2001): 20–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163421.

[7] Crawford, L. “James Monroe’s Trail of Tears.” The J. M. Museum. (2022) https://jamesmonroemuseum.umw.edu/2022/11/28/james-monroes-trail-of-tears/

[8] Schoffen, Elizabeth. The Demands of Rome: Her Own Story of Thirty-One Years as a Sister of Charity in the Order of the Sisters of Charity of Providence of the Roman Catholic Church. Published By Elizabeth Schoffen (1917): 44 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/37104/37104-h/37104-h.htm

References Continued

[9] Newland, Bryan “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report Vol.II,” Indian Affairs(2024)https://www.bia.gov/sites/default/files/media_document/doi_federal_indian_boarding_school_initiative_investigative_report_vii_final_508_compliant.pdf?itid=lk_inline_enhanced-template. National Archives. “Native American Heritage: Bureau of Indian Affairs Boarding School Records. at the National Archives in Washington, DC.” (1790 – 1950) https://www.archives.gov/research/native-americans/schools/headquarters-records?itid=lk_inline_enhanced-template. Dana Hedgpeth, Sari Horwitz, Joyce Sohyun Lee, Andrew Ba Tran, Nilo Tabrizy and Jahi Chikwendiu. “More than 3,100 students died at schools built to crush Native American cultures” The Washington Post, (2024) https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/interactive/2024/native-american-deaths-burial-sites-boarding-schools/

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Mills, Kadin “We Survived, We Are Resilient’: Remembering U.S. Indian Boarding Schools.” NPR.(2025) https://www.npr.org/2025/09/30/nx-s1-5552527/remembering-u-s-indian-boarding-schools.

[13] Meriam, Lewis., Frank C. Miller (1971 addition) “Meriam Report: The Problem of Indian Administration” The John Hopkins Press., National Indian Law Library,(1928) https://narf.org/nill/resources/meriam.html

[14] National Archives, “Native American Heritage: Records Relating to the Indian Reorganization Act (Wheeler–Howard Act)” (1934) https://www.archives.gov/research/native-americans/indian-reorganization-act

[15] 95th Congress (1977-1978), “S.1214 – Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978.” Senate – Indian Affairs (Select): House – Interior and Insular Affairs. https://www.congress.gov/bill/95th-congress/senate-bill/1214

[16] “List of Indian Boarding Schools in the United States,” Boarding School Healing, (2025) https://boardingschoolhealing.org/list-of-indian-boarding-schools/

[17] Brewer, Graham Lee. “Biden makes historic apology for ‘sin’ of U.S. role in deadly Indigenous boarding schools,” PBS, 2024 https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/watch-live-biden-to-make-historic-apology-for-u-s-role-in-deadly-indigenous-boarding-schools

Don't miss a beat!

Be part of the EDH Family and Join our Newsletter for exclusive discounts and life changing strategies. Plus get the Family Activities Handbook PDF download straight to your inbox today!

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.