How Taylor, a Slave Girl, Illegally Taught Soldiers to Read

Dec 15, 2025Enslaved and Law-Breaking Beginnings

There are often figures in history who have made a big difference, but have seldom been acknowledged for their great contribution to society. Susie King Taylor is one such woman. Taylor was Born into slavery, August 6, 1848, in coastal Georgia. There were restrictive laws on education for freed and enslaved African Americans. Anyone found teaching a slave to read and or write was at risk of lawful punishment. Likewise, if a slave was found reading or writing they would be punished, however their punishment was more severe.

At the age of seven Taylor was permitted to move in with her grandmother in Savannah, Georgia. Taylor’s grandmother encouraged her to learn to read and become educated and arranged for her to attend clandestine schools.[1] By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, Taylor was so well educated she had surpassed the level of knowledge of her first teachers in Georgia.

The Escape from Slavery

Taylor returned to her mother in 1862, an educated young woman. At this time the civil war had been going on a year already. Taylor, and her family, hoped that the ‘Wonderful Yankees’ would “set all the slaves free.”[2] Their hopes were realized April 1, 1862, when Union forces attacked the Confederate-held Fort Pulaski. Taylor remembered the experience saying:

“I remember what a roar and din the guns made. They jarred the earth for miles. The Union [the Yankees] had taken the fort at last.”[3]

It was during the chaos of the battle that Taylor and her uncle’s family made their escape. They travelled on a Union Ship where, Taylor’s reading, writing, and masterful sewing abilities—skills often not taught to women of color in the South, impressed Lieutenant Pendleton G. Watmough.

“He was surprised by my accomplishments (for they were such in those days), for he said he did not know there were any negroes in the South able to read or write.”[4]

Watmough then aided Taylor in finding a teaching position where she taught many children and adults.

“[They] came to me nights, all of them so eager to learn to read, to read above anything else.” [5]

At just 14 years of age, Taylor had become the first African American known to teach at a freedmen’s school in Georgia.

Taylor’s Work in the Army

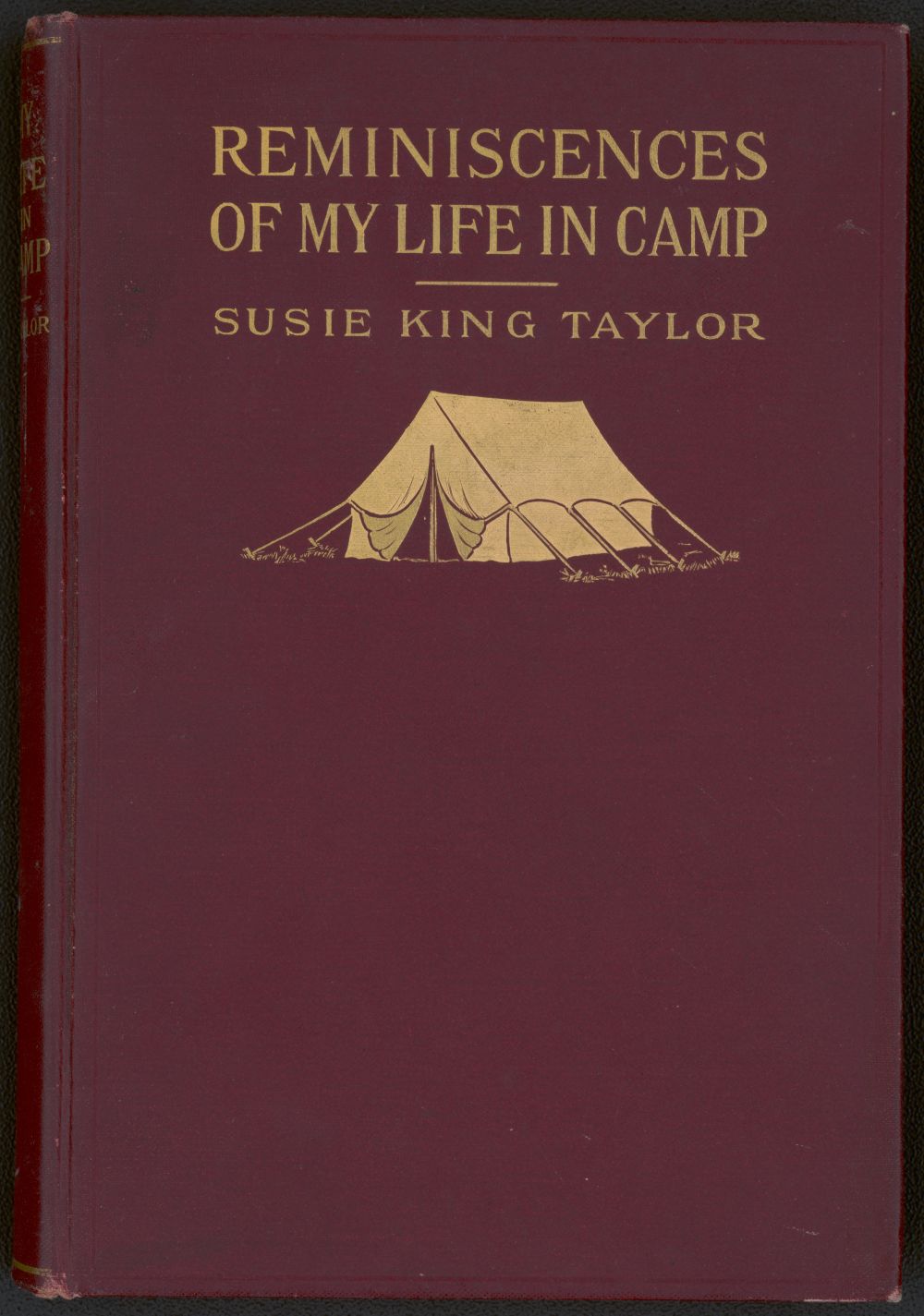

In her book Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, published in 1902, she recounts her experience as a nurse, caretaker, educator and friend to the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. She stated:

“There are many people who do not know what some of the colored women did during the war.”[6]

Taylor was able to fire muskets clean them and take them apart before putting them back together again.[7]

“I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day… I thought this great fun. I was also able to take a gun all apart, and put it together again.”[8]

- Reminiscences of My Life in Camp. By Susie King Taylor, 1902

What was she really

In the late fall of 1862 Taylor became a “laundress” for the Union Army but her duties far exceeded that of a cleaning lady. She said:

“I was enrolled as company laundress, but I did very little of it, because I was always busy doing other things through camp, and was employed all the time doing something for the officers and comrades.” [9]

Taylor states:

“I taught a great many of the comrades in Company E to read and write, when they were off duty. Nearly all were anxious to learn… I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services… Our boys would say to me sometimes ‘Mrs. King, why is it you are so kind to us? you treat us just as you do the boys in your own company…you took an interest in us boys ever since we have been here, and we are very grateful for all you do for us.’”[10]

A Technicality of Monetary Value

In a 1902 letter republished in Reminiscences,[11] Colonel Trowbridge, commander of the First South Carolina Volunteers, apologized for the “technicality” of Taylor’s identification as only a laundress, rather than a nurse. Taylor thought highly of Trowbridge: “We thought there was no one like [Trowbridge], for he was a ‘man’ among his soldiers… I shall never forget his friendship and kindness toward me, from the first time I met him to the end of the war… No officer in the army was more beloved than our late lieutenant-colonel.”[12]

His apology was likely due to the fact that such a “technicality” led to Taylor never receiving pay or a pension. The general public and army did not look upon Laundresses favorably, as most of the women who worked as Laundresses were illiterate and stereotyped as “loose women.”

How we recognize taylor today

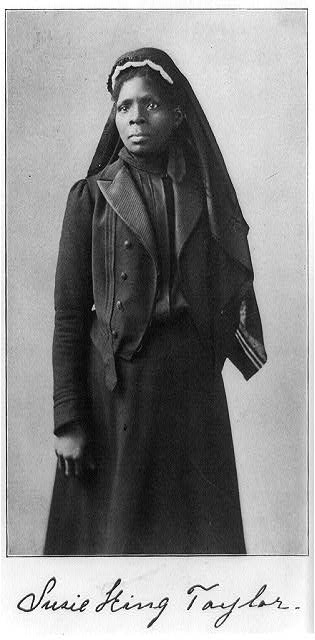

Today Taylor is more commonly recognized as the first African American Army nurse, and not as a laundress. Taylor spoke of her nursing experience saying:

“It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war,—how we are able to see the most sickening sights, such as men with their limbs blown off and mangled by the deadly shells, without a shudder; and instead of turning away, how we hurry to assist in alleviating their pain, bind up their wounds, and press the cool water to their parched lips, with feelings only of sympathy and pity.”[13]

Taylor’s nursing duties extended beyond the work she did in the regiment camps. She often visited nearby hospitals to provide aid in any way she could. It was in a Beaufort hospital that Taylor met Clarissa Harlowe Barton, an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse, teacher, and patent clerk at the time of the American Civil War.

“When at Camp Shaw, I visited the hospital in Beaufort, where I met Clara Barton. There were a number of sick and wounded soldiers there, and I went often to see the comrades. Miss Barton was always very cordial toward me, and I honored her for her devotion and care of those men.”[14]

- Susie King Taylor, Known as the First African American Army Nurse. United States, 1902.

The Civil War and Escape Slave Involvement

The Union army would send runaway slaves back to their owners in the South, early in the war. However, this changed when they decided to classify escaped slaves as “contrabands of war,” which meant there was no legal obligation to return them to the Confederates. Escapees became the property of the Union Army. Under this new label, Escapees were forced to work as laborers. As the war went on, it became clear to the Union that more soldiers were needed to win the war. So, the former slaves became military laborers. This changed again by the fall of 1862, when African Americans were no longer considered property by the Union. African Americans were allowed to voluntarily enlist—albeit under segregated units—without fear of being forced into servitude. Colonel Higginson in Leaves from an Officer’s Journal, in the fall of 1862 wrote:

“… the aptitude of the freed slaves for military drill and discipline, their ardent loyalty, their courage under fire, and their self-control in success, contributed somewhat towards solving the problem of the war, and towards remolding the destinies of two races on this continent.”

The 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment was formed in November 1862. Abraham Lincolin signed the Emancipation Proclamation two months later in January 1863. The Proclamation allowed the Union Army to formally recognize African American infantries. Taylor recalled:

“On the first of January, 1863, we held services for the purpose of listening to the reading of President Lincoln’s proclamation…and the presentation of two beautiful stands of colors… It was a glorious day for us all, and we enjoyed every minute of it…many, no doubt, dreamt of this memorable day.”[15]

The End of the Civil War

The infantry Taylor was part of, mustered out in early 1866. Taylor and her husband, Edward King, never received a pension for their services, unlike their white comrades. King, was a carpenter. After the war, King was unable to secure a job in carpentry, due to the segregation laws that pervaded the South. These laws made life extremely challenging and dangerous for African Americans. He died in a docking accident late 1866, before his first son was born. Between 1866 and 1868 Taylor opened and taught in the three separate schools, two in Savannah and one in Georgia.

Taylor was unable to compete with the free schools that the state governments were opening for African Americans. So, in order to support her son and herself she quit teaching in 1868 and picked up work as a domestic servant. To enable Taylor to travel North and South for work, she left her son in her mother’s care.

Final Thoughts

Taylor’s experience makes it clear that there was an eagerness to read among African Americans, and that given the opportunity they had the initiative and desire to persevere even at the risk of breaking the law. African Americans have also shown their strength and intellect through educating themselves, curtailing the law and building themselves up even with an unaccepting society around them. Taylor said:

“I wonder if our white fellow men realize the true sense or meaning of brotherhood? For two hundred years we had toiled for them; the war of 1861 came and was ended, and we thought our race was forever freed from bondage, and that the two races could live in unity with each other, but when we read almost every day of what is being done to my race by some whites in the South, I sometimes ask, ‘Was the war in vain? Has it brought freedom, in the full sense of the word, or has it not made our condition more hopeless?’”[16]

This statement speaks volumes about the state of post-war America and the continued mistreatment of Black Americans. Taylor spent much of her post-war life with the Woman’s Relief Corps, Auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic and organized Corps 67, to aid veterans and their families.[17]

Taylor passed away in October 1912.

What was it all for? Taylors connection to compulsory schooling

Taylor likely did not know of the ideas behind mandatory schooling though she knew there were systemic issues. Compulsory schooling made life harder for Taylor. Such free institutions rendered her services and business expensive in comparison. Taylor taught her students with a sense of encouragement, equipping them with needed skills. The states and government have designed the mandatory schooling system to discourage true education and only equip students with the necessary skills for service in factories, offices and other laborious endeavors. Such intentions become apparent when looking into the origins of compulsory schooling. (read about the dark roots of the American schooling system here)

References

[1] Clandestine Schools – planned, done in secret and not officially allowed.

[2] Taylor, Susie K. Reminiscences of My Life in Camp: with the 33d United States colored troops, late 1st S. C. Volunteers. Susie King Taylor. (1902) : 8 https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/taylorsu/taylorsu.html

[3] Ibid: 8-9

[4] Ibid: 9

[5] Ibid: 11

[6] Ibid: 67

[7] Ibid: 26

[8] Ibid: 26

[9] Ibid: 35

[10] Ibid: 21, 29-30

[11] Ibid: xiii

[12] Ibid 45-46

[13] Ibid: 31-32

[14] Ibid: 30

[15] Ibid: 18

[16] Ibid: 61

[17] Ibid: 59

Additional References

Reminiscences of My Life in Camp. By Susie King Taylor, 1902. https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.67943

Susie King Taylor, Known as the First African American Army Nurse. United States, 1902. [Boston: Published by the author, from a photograph taken earlier] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003653538/.

Library of Congress. “Susie King Taylor: An African Nurse and Teacher in the Civil War.” https://www.loc.gov/ghe/cascade/index.html?appid=5be2377c246c4b5483e32ddd51d32dc0&bookmark=Battlefront%20Words

Don't miss a beat!

Be part of the EDH Family and Join our Newsletter for exclusive discounts and life changing strategies. Plus get the Family Activities Handbook PDF download straight to your inbox today!

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.